A Short History of the SECR

Whilst a relatively small system serving a compact and largely self-contained area, the SECR presents the historian or modeller with a microcosm of Britain’s railways — something of everything. In engineering and operational terms, especially in its later years, the SECR was one of the most innovative companies, and its influence could be seen not only in the Southern Railway but well into the BR period. Some of its exceptionally long-lasting locomotives and coaching stock added interest against the backdrop of later standardisation, often working far outside the territory of their parent company on branch lines from Sussex to Devon.

The SECR was formed in 1899 by the legal union of two existing companies: the South Eastern Railway and the London, Chatham & Dover Railway, whose rivalry had been damaging to profits and investment. Although the two companies remained distinct legal entities, and their buildings and structures bore witness to their respective origins, their rolling stock soon began to mix, adding variety to the scene. The SECR’s own locomotives and rolling stock began to be introduced, but for at least a decade, there remained a great variety of locomotives and rolling stock from pre-1899, many of which were still in service at the 1923 Grouping. Buildings, too, were immensely varied, from the grand London termini of Victoria and Cannon Street to humble country stations in weatherboard. Many brick buildings still exist, showing the clear difference in styles between those of the SER and LCDR.

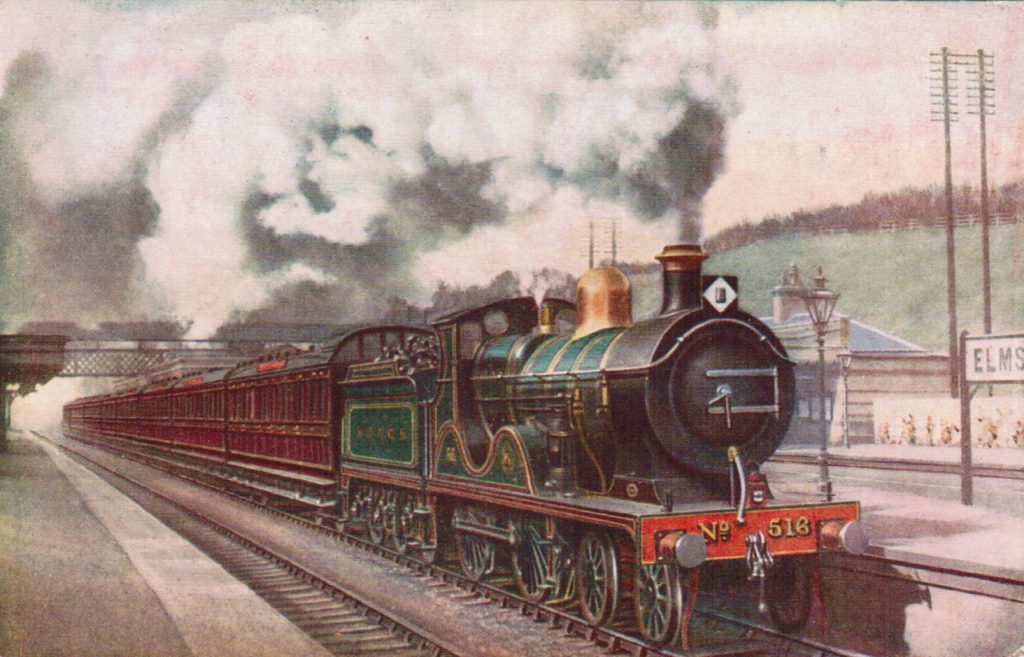

The SECR’s most glamorous trains were, of course, the continental expresses working to Dover and Folkestone to connect with the Channel ferries. In the London area, it operated some of the most complex steam commuter services in the country. Elsewhere, its lines saw not just local trains but fast passenger services serving the residential areas of Hastings, Folkestone, and the Kent coast. Cross-country trains to and from other railways, such as the Great Western, Midland, and London & North Western, sent some of the best SECR coaching stock onto those foreign railways, whilst in return, their stock added variety to the Kent scene. Other passenger traffic included seaside excursions and the annual migration of Londoners to Kent for hop-picking, both of which saw a variety of the oldest vehicles pressed back into service.

While the tonnage of freight was much less than on railways serving the coalfields and industry of Britain’s Midlands and North, the SECR offered a considerable variety of traffic carried in distinctive wagons and vans, attractive to modellers. Agricultural produce featured largely, along with perishable or valuable Grand Vitesse traffic from continental Europe. The SECR also served a variety of heavy industries and military establishments beside the Thames and in the Medway Valley, as well as coal from the East Kent coalfield. Transfer freights to and from other railways north of the Thames passed through some of the busiest parts of the suburban area by way of the Snow Hill tunnel (now Thameslink) or the East London Line (now part of the London Overground network), bringing the wagons of foreign companies into Kent, with their locomotives as far as the marshalling yards at Herne Hill and Hither Green.

As the railway serving the principal Channel ports, the SECR played a key role during the Great War, with trains for forces on leave and for the wounded making use of the fine new marine station at Dover, where the company’s War Memorial would eventually be placed. The military’s need for equipment and supplies added to freight traffic, with much being despatched via the pioneering train ferry operating from Richborough, while the railway’s works were employed in the manufacture of spare parts for French and Belgian locomotives, as well as some purely military items.

Harry Wainwright was the Chief Mechanical Engineer from the union in 1899, and, while he was responsible for much-needed improvements in coaching stock, new locomotive designs tended to build on the traditions of the LCDR. During his tenure, locomotives and coaching stock displayed high standards of appearance and presentation, with the “full Wainwright” livery for locomotives being one of the most elaborate and decorative to be seen in the UK, until it was simplified just before the Great War and eventually replaced with plain greenish-grey. Similarly, coaching stock was of neat appearance, attractively painted, lined, and lettered, at least until the plain brown livery of the war years replaced Wainwright’s crimson lake.

From 1913, Richard Maunsell made the SECR one of the most technically advanced and innovative lines in the country, bringing some of the Great Western’s foremost draughtsmen into his team to tap the experience built up by that company. One of these, Harold Holcroft, was responsible for much advanced thinking on the subject of multi-cylinder locomotives and developed the simple and elegant “2 to 1” conjugated valve gear for 3-cylinder locomotives that was later adopted by Gresley to become a lasting feature of his LNER Pacifics. Maunsell’s own rebuilds of the Wainwright E and D Class locomotives with large piston valves provided locomotives for the continental expresses that were probably unrivalled for their size, while his N Class 2-6-0 was adopted by the Government to be built at Woolwich Arsenal after the restoration of peace in 1918 to keep munitions workers employed. Derivatives of this design appeared not only on the Southern Railway but also on the Metropolitan Railway and in the Republic of Ireland.

The SECR was one of the first railways to build coaches for ordinary use as long as 60 feet, while the highest standards of accommodation persisted in the unusual match-board sided “continental” stock. Its trains were often enlivened by Pullman cars, whether forming continental expresses or working singly in the residential services to provide catering for City commuters or businessmen weekending on the Kent Coast. These Pullmans always carried the crimson lake livery of the Wainwright period, even after ordinary coaching stock was repainted in a simple brown during the Great War.

Coaches of SECR origin were robustly built and saw service on other parts of the Southern Railway, including the Isle of Wight, where they worked until the end of steam in 1966. Several have been preserved both there and on the mainland. The “birdcage” guard’s lookout, driven by width restrictions and the need to use every inch of train productively, persisted as a feature of SECR coaching stock, with the last coach so fitted being withdrawn as late as 1962.

The SECR’s own electrification plans never bore fruit during its lifetime, but its suburban routes were amongst the first to be dealt with by the Southern Railway. In fact, much of the electric coaching stock was formed from the bodies of the best steam-hauled coaches from the late 19th century, placed on new underframes. So robust and serviceable were these bodies that the “new” coaches formed from them lasted well into the BR period.

The SECR’s capacity for innovation extended into signalling, where the 3-position semaphore signals installed at Victoria were, in their time, truly cutting edge. As were the 4-aspect colour light signals installed on other lines in the London area by the Southern Railway. Operationally, the 1922 “parallel working” timetable, which structured the mix of suburban and long-distance trains around the focal point of Borough Market Junction, was an achievement to rival the intensive but relatively simple and self-contained “Jazz” services of the GER. The pattern of parallel moves across Borough Market Junction set a structure in the timetable that could still be seen as late as 1975 when BR’s remodelling of the London Bridge area simplified the track layout that the SECR had had to work with.

Thus, the SECR presents the modeller with many opportunities for unusual or eye-catching scenes, whether it be long-lasting locos and coaches adding interest and variety to a BR or Southern Railway period layout, or the contrast between pick-up freight trains and glamorous continental expresses, suburban trains, and cross-London freight trains hauled by other companies’ locomotives on the same metals. If it happened at all, it probably happened somewhere on the SECR!